Buildings are more than concrete, steel, and brick. They reflect our values. And so it is with a new graduate-student residence hall at Yale University’s Divinity School, seeking full certification under the Living Building Challenge (LBC), a green building-rating system widely regarded as the world’s most rigorous. Gregory Sterling, Divinity School dean, decided the project should be designed to the “Living” standard more than a decade ago, after learning about the Challenge from a trustee. Reading the introductory text of the rating system, it is easy to understand how the program would resonate with a client such as a divinity school. It asks us to imagine the creation of “homes, workplaces, neighborhoods, villages, towns and cities (that are) socially just, culturally rich and ecologically restorative.” It poses such existential questions as “What if every single act of design and construction made the world a better place?” It is no surprise, then, that in the LBC program, Sterling found remarkable alignment with a philosophy known as eco-theology. It is the conviction “that we as humans are part of God’s creation and are responsible and answerable to God in how we treat it,” he explains. “Rather than masters of creation, we are stewards of it.”

The product of this LBC process, the 50-bed Living Village, was completed in August. The terra-cotta-rainscreen-clad structure sits on New Haven’s Science Hill, about a mile and a half from the center of the Yale campus. It occupies the site of a former parking lot, directly to the north of the Divinity School’s historic Delano & Aldrich quadrangle, a 1932 Georgian-style complex modeled after Thomas Jefferson’s design for the University of Virginia. As at the “academical village” in Charlottesville, two rows of brick pavilions define a central lawn, but with a steeple-topped chapel at its head instead of Jefferson’s domed Rotunda. The scheme for the three-story building (four stories to the east, where the ground steeply slopes), was developed by a collaborative team that included architecture firms Bruner/Cott and Höweler + Yoon and landscape architect Andropogon. It plays on the courtyard typology, defining a grass-covered outdoor room with its U-shaped footprint and one leg of the historic quadrangle, “extending the logic beyond the original,” says Eric Höweler, Höweler + Yoon cofounder.

The eastern side of the building includes a shared terrace, directly outside a community kitchen, and a stepped lawn with seating. Photo © Robert Benson, click to enlarge.

There are other contemporary takes on the Living Village’s neighbor, including the photovoltaic (PV) tile-covered roof, subtly twisted to optimize energy production (more about this later) and to create a dialogue with the slate-roofed Delano & Aldrich complex. The terra-cotta cladding references the historic pavilions’ mostly unadorned brick, while white-glazed panels at the Living Village’s northwest corner frame an entry portal and recall the whitewashed masonry in some areas of the historic quadrangle.

The white-glazed terra-cotta of the entry portal refers to the whitewashed masonry of the historic quadrangle. Photo © Robert Benson

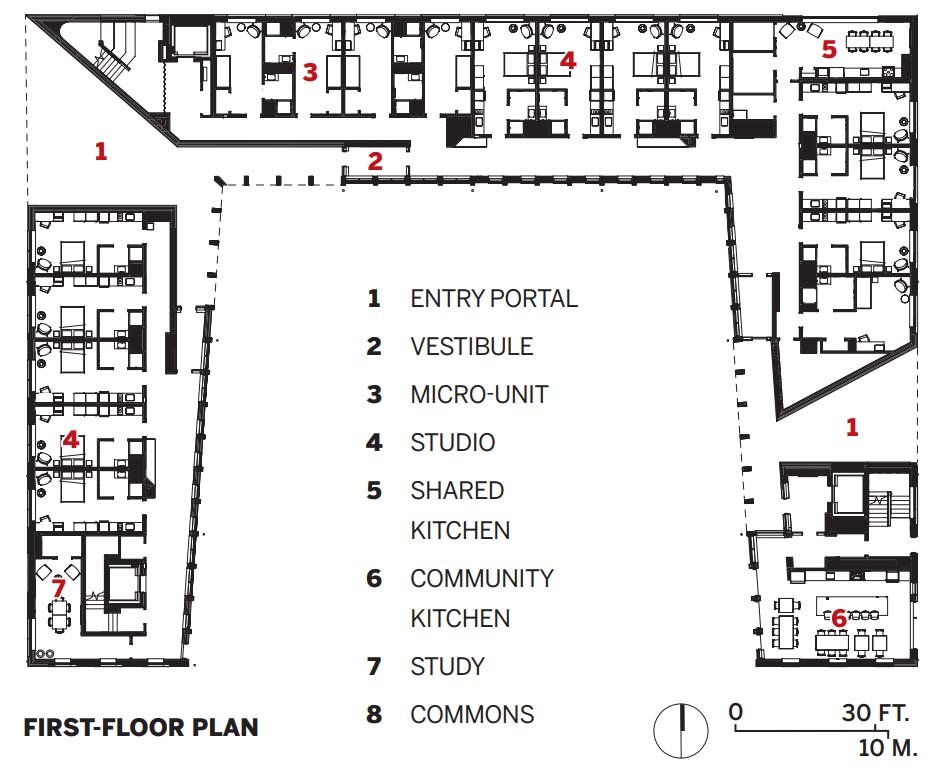

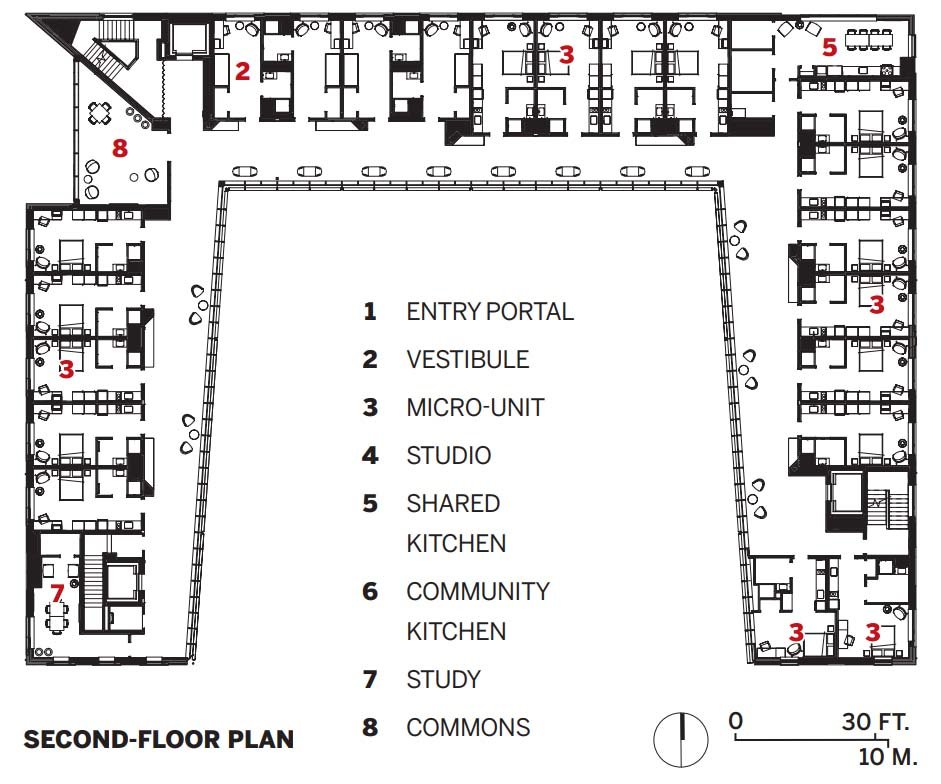

Supported by a hybrid structure combining mass timber and conventional wood framing, the building has been organized to prioritize shared space, including lounges, and group kitchens and dining areas. The apartment types range from micro-units (one-person living spaces with baths, but no kitchens) to more fully equipped, but still quite compact, two-bedroom apartments for students with families or for visiting scholars. The monastic-scale units wrap a hallway—one generous enough to double as a place for studying, relaxing, or socializing, and with views through floor-to-ceiling windows onto the central courtyard. Although such single-loaded corridors are atypical at Yale, they were embraced here. “The message from the client” says Jason Jewhurst, Bruner/Cott principal, “was that every space outside the dwelling units should support community.”

1

2

Hallways double as social spaces (1) and face a courtyard framed by the new building and the historic complex (2 & 3). Photos © Robert Benson

3

At 45,000 square feet, the Living Village is expected to be the largest residential building fully certified under the LBC program, which is overseen by nonprofit organization the International Living Building Institute (ILFI). The building is on track to be part of an extremely rarefied group: since the Challenge’s launch in 2006, only 35 projects of any type have achieved full Living status. To do so, they have demonstrated compliance with 20 tough-to-achieve “imperatives,” organized into seven “petals,” or performance areas: place, water, energy, health + happiness, materials, equity, and beauty.

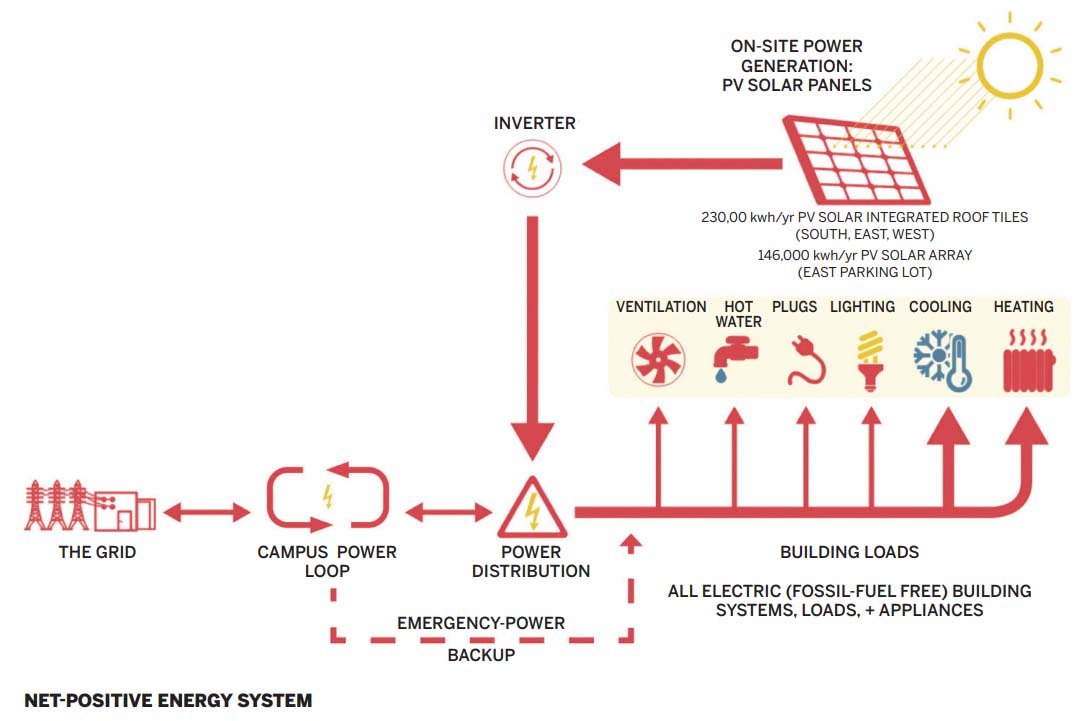

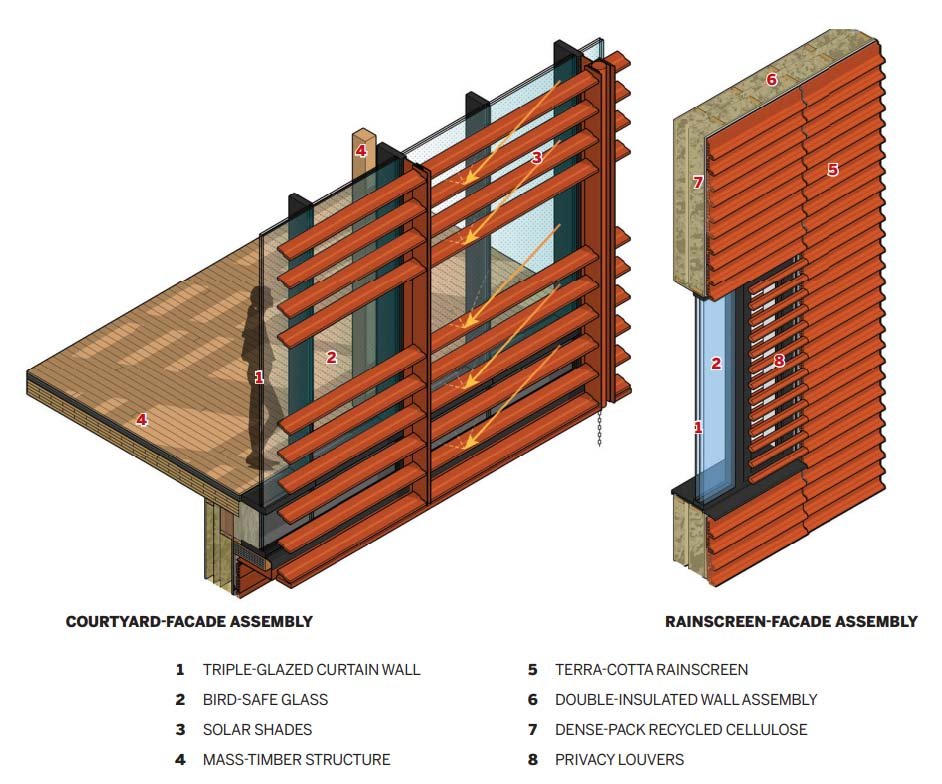

One of the imperatives is for net-positive energy, requiring that projects generate at least 105 percent of their power needs from renewable sources on-site, without reliance on the combustion of fossil fuels. At the Living Village, the roof shape, which resembles a conventional gable at the U’s two southern ends, has been cleverly manipulated to eliminate any north-facing surfaces and therefore maximize the output of its integrated PVs. The architects estimate that the roof will generate 230,000 kilowatt hours (kWh) of electricity annually. A second solar array, planned as a canopy over a nearby parking lot, is projected to generate another 146,000 kWh each year. The project team expects that the two sets of PVs—combined with efficiency measures such as a superinsulated and airtight envelope, triple-glazed windows, and mechanical strategies that include air-source heat pumps, a dedicated outdoor-air system, and heat recovery—will allow the Living Village to comfortably meet the LBC’s net-positive threshold.

Image courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

Many of the imperatives extend beyond the boundaries of the building. In fact, more than 75 percent are dependent on integrated site and landscape strategies, says José Almiñana, Andropogon principal. He points to an imperative for urban agriculture, for instance, whose goal is to connect inhabitants and the community to locally grown fresh food. To satisfy the requirement, the Living Village includes a kitchen garden and an orchard—in addition to the already established Divinity Farm, to the east of the Living Village site. Food-producing plants are also distributed throughout the landscape. Just one example are the shadbushes planted in the courtyard, which grow berries that appeal to birds as well as humans. “The LBC’s idea of food is biocentric, not just anthropocentric,” says Almiñana.

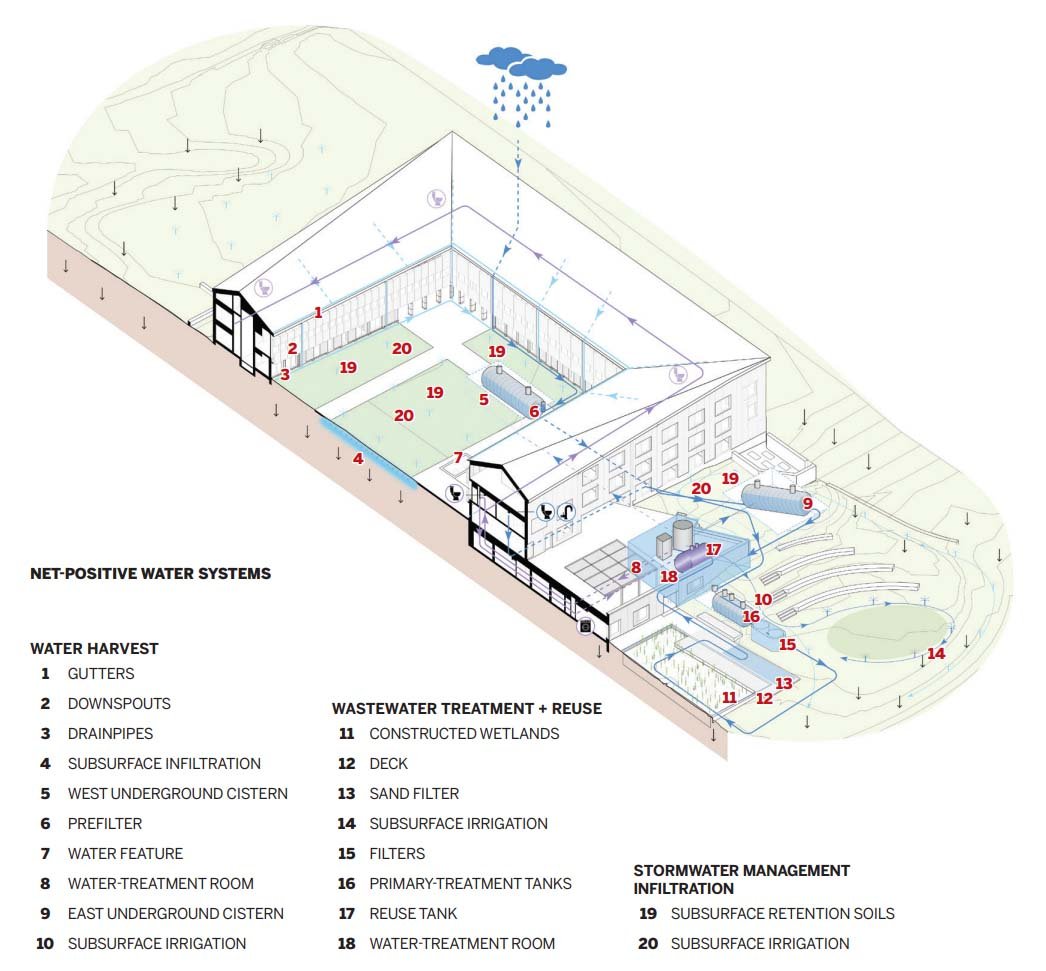

Landscape was also integral to achieving the imperatives relating to water—the most complex of all the LBC requirements, says the design team. The intent of these requirements, according to LBC, is to realign how people value water, address the energy and chemicals involved in its transportation and treatment, and redefine wastewater as a resource. To comply, the project incorporates three separate systems for water conservation and reuse, and for restoration of the site’s hydrological ecology. One collects water from sinks, showers, laundry, and toilets and purifies it for subsurface landscape irrigation and for flushing toilets. The process includes a series of filters, UV treatment, and a constructed wetland powered by the sun and photosynthesis. Planted with grasses with robust root systems, the wetlands break down organic matter and nutrients such as nitrogen.

A second system manages stormwater, collecting the rain that falls on the building’s roof, filtering it to supply a courtyard water feature and as another source for irrigation, and for infiltration into the ground to help replenish the water table. To aid the infiltration process and avoid overtaxing New Haven’s combined-sewer system, the landscape has been designed to retain a quantity of water equivalent to that of a 100-year storm, or 9.6 inches of rainfall in 24 hours—or about five times the retention capacity required by the city, according to the architects.

The most challenging of the water stipulations was the one involving drinking water. Officially, at least, a Living project must satisfy its water needs—including those for potable uses—entirely through “captured precipitation or other natural closed-loop water systems, and/or through recycling used project water.” In the case of the Divinity School, complying with the letter of the rating system would have meant establishing its own water authority and would have required additional treatment equipment costing about $1 million, with another $150,000 needed annually to operate it, according to Sterling. But, instead, ILFI allowed the Living Village to follow an alternate compliance pathway and obtain its drinking water from a nearby utility. The agreement includes removing the supply’s chlorine at every tap and, in addition, the donation of 90 low-flow showerheads to a New Haven nonprofit that operates shelters for the homeless, thereby reducing the water consumption of its housing. The school has also agreed to establish advocacy programs for regional water-related concerns. The donation of the showerheads and the advocacy work are illustrations of “handprinting,” a strategy central to LBC that, in contrast to “footprinting,” emphasizes the positive environmental effects of projects or practices.

Image courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

One particularly labor-intensive part of designing any Living project is the vetting of building products for conformance with the certification system’s extensive materials-selection criteria. These include limits on the distances that components can be shipped—a restriction intended to reduce the energy embodied in materials and spur the development of a regional green economy. The standard also mandates that a project avoids the use of 19 classes of chemicals on the LBC Red List—many of which are commonplace in building products, including vinyl, antimicrobials, and volatile organic compounds. The idea is to ensure a healthy environment for occupants, reduce pollution and resource depletion, and provide an incentive for market transformation. The hope is that the requirements will encourage manufacturers to examine and modify their supply chains.

The architects estimate that they vetted close to 3,000 products before ultimately selecting the approximately 1,000 that have been used in the Living Village. Of those, roughly 50 percent were sourced within 600 miles of the site. One especially notable outcome of the process, says Jewhurst, is that 30 manufacturers were motivated to disclose product ingredients through ILFI’s own Declare label or through the program run by the Health Product Declaration Collaborative, another nonprofit. These new disclosures make ingredient information, which companies typically hold closely as trade secrets, available to other design teams, easing the pathway to certification. “The project inspired those manufacturers to get out in front of the documentation,” he says.

The Living Village is not yet certified. Before this can happen, the team must submit 12 months of water- and energy-performance data. But the verification period can’t begin just yet: the university is still waiting for its permit to start operating its graywater system, and the PV canopy over the parking lot has yet to be installed. Nevertheless, Sterling is already thinking about the next project. He plans to start fundraising soon for a replacement for another student residence—an 84-unit, nearly 70-year-old apartment building with antiquated infrastructure. Ultimately, he hopes to certify the entire Divinity School campus. Clearly a devout LBC convert, he is spreading the gospel.

Image courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

Image courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

Image courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

Credits

Architect:

Bruner/Cott Architects — Jason Jewhurst, principal in charge; Gretchen Neeley, George Gard, project managers; Carolyn Creemers, project architect; Karen Greene, consulting associate for interior architecture; Madison Rogers, project designer; Megumi Miyaoka, designer, LBC documentation; Ruoxi Yang, designer

Design Architect:

Höweler + Yoon Architecture — Eric Höweler, principal in charge; Meejin Yoon, principal; Kyle Coburn, project manager; Ching Ying Ngan, Josue Perez Campos, Joel Wan, designers

Consultants:

Andropogon Associates (landscape); van Zelm Engineers (m/e/p/fp); Silman/TYLin (structural); Biohabitats (wastewater/stormwater); Nitsch Engineers (civil); Haley & Aldrich (geotechnical); New Frameworks (embodied carbon); Materially Better (LBC/materials); McLennan Design (biophilic design); Craul, Land Scientists (soils); Aqueous Consulting (irrigation)

General Contractor:

Shawmut Design and Construction

Client:

Yale Divinity School

Size:

45,000 square feet

Cost:

$67 million (construction)

Completion Date:

August 2025

Sources

Rainscreen:

Boston Valley Terra Cotta

Curtain Wall:

Kawneer

Roof Shingles:

Luma Solar

Terrace Roofing:

GAF

Fiberglass Windows:

Cascadia Windows & Doors

Glazing:

Guardian Glass

Skylights:

Velux

Acoustical Ceilings:

Armstrong World Industries

Plastic laminate:

Wilsonart

Solid Surfacing:

Corian, Caesarstone

Elevators:

Otis

Plumbing Fixtures/Fittings:

Toto, Chicago Faucet, Moen, High Sierra

Rainwater and Wastewater Tanks:

Xerxes

Continuing Education

To earn one AIA learning unit (LU), including one hour of health, safety, and welfare (HSW) credit, read the article above and Living Building Challenge 4.1 Program Manual, July 2025 — Last update: 9 September 2025, International Living Future Institute (through page 26). Then complete the quiz.

Upon passing the quiz, you will receive a certificate of completion, and your credit will be automatically reported to the AIA. Additional information regarding credit-reporting and continuing-education requirements can be found at continuingeducation.bnpmedia.com.

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the goals of the Living Building Challenge, its structure, and certification requirements.

- Discuss concepts and terminology central to the Living Building Challenge, such as “imperatives” and “handprinting.”

- Describe the three different water systems employed at Yale’s Living Village and explain how they function and how they satisfy the certification system’s requirements.

- Explain the strategies employed by the Living Village for meeting the certification system’s net-positive energy requirement.

AIA/CES Course #K2512A

Quiz link coming soon